Breaking the fourth wall.

Why would kids actively enjoy steeping themselves in the worlds of happy-go-lucky characters whose lives are disrupted and ripped apart instead of being creeped out and scared? How is it that a character like Sans the skeleton is so beloved by children today when Mario speaking with a harsh Brooklyn accent disgruntled kids so much that Nintendo had voice actor Charles Martinet totally change course?

Kids are inundated with waves of waves of media aimed at, marketed towards, and focus tested to appeal broadly. Games like Undertale represent postmodern takes on game design—appealing for those looking to break out of the commercial mould– not only promoting active discussion of theories and lore (an alternative to Minecraft’s literal world-building), but they let players choose to explore that dark side in a way that is safe and manageable.

I know what you did

Editor’s note: This section contains spoilers for Undertale.

When I tried out Undertale it was based on some out of context bits of the game I was seeing popular YouTubers upload. My only real knowledge of the game going into it was that it had a wry dark side to match its goofy humor, and that it was a turn-based RPG where no one had to die.

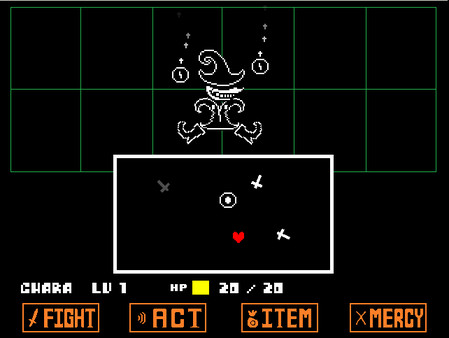

Within the first thirty minutes, after navigating the Ruins and avoiding harming so much as a fly, I was confronted with the game’s first boss fight. Unsure of what to do after a while, I fought back, assuming I’d weaken her and be able to move past.

That…wasn’t the case.

I killed her.

It felt terrible, in a way that most RPGs fear making the player feel, focusing on her mangled, bloody expression before she faded into literal dust.

I rebooted the game. I reloaded my save file. I fought her again and I just avoided her attacks for as long I could. She gave up, at long last, and let my player character pass.

It was at this moment that the game truly sank its hooks into me as the deceptively cute antagonistic flower who met me in the next room taunted me.

“You think you’re really smart, don’t you?” he taunted. “I know what you did.”

My gut shrivelled as my mind reeled with intrigue. Did he know what I did?

“You murdered her. And then you went back because you regretted it.”

Image: tobyfox

Indeed, that was exactly what had transpired – from my point of view and in my reality.

In this moment I truly started understanding that Undertale is something else, something special, something exploring an idea I longed to see games touch on, and something that has become a bit of a trend since.

It is a unique achievement for such a small game to manage, but what has perhaps surprised me most about it, and games like it, is just how pervasive the game and others of its kind have been on younger generations.

It’s human nature to fear the unknown, to shape in our minds something more cruel from shadows than what is exposed in light, and worlds like this in an interactive medium allow players to engage with those shadows, shine a light on them, and acknowledge that they are part of the world, because games – like all art – don’t exist in a vacuum.

The Underground

Players feel more personally connected to a world that itself identifies as a pocket dimension, a singular instance of an alternate reality that each of us explores and affects by our choices. It highlights the power of human choice both in and out of fictional realities. Games like Minecraft and Fortnite bake this personal connection into literal world-building in the player’s hands, while Undertale offers open-ended narrative settings with surprisingly complex consequences for players to mull over and remix.

On another Undertale run, I set about actively murdering everything – systematically, as one is encouraged to do in a classic JPRG, grinding to increase numerical stat values – and the game revealed a raw, uncomfortable darkness to it that reflected my own actions in the game in a manner which felt much truer to reality than any other RPG I had played.

It even called me out on my motives – I was doing it just to see what would happen, just to experience the dark side of its world myself. I could have looked up a video – and indeed, the game even calls out those who are doing as such – but I chose to sow seeds of death and destruction out of morbid curiosity.

And while I was rewarded with one of the toughest and most brilliant boss fights ever envisioned in a game, I couldn’t undo the fact that in my reality, I actively chose to destroy this fictional world.

When we’re given the opportunity to shine light on sinister shadows, we’re far more often going to accept what is revealed and reconcile with it than we are to continue cowering before it. In a medium built on bloodshed – even if the blood is invisible and the consequences seemingly non-existent – it’s empowering and connecting to be offered experiences where players can feel their choices as players and participants directly impacting a fictional world they inhabit. Ideally, this will lead to forming connections in their own reality and carrying with them the weight of choice and consequence outside of the fictional reality and into our own.

Desma Palmer Fettig is a former retail worker, storyteller, and amateur visual novel developer who grew up in western New York, lived in the SF Bay Area, and now resides in Southern England.