With the release of Persona 5: Royale, we reflect on the real life lessons learned in the game.

Content Warning: The game featured is rated M by the ESRB for blood, drug references, partial nudity, sexual themes, strong language, and violence. The prominence of the game’s protagonist in Super Smash Bros Ultimate (T) and the recent ‘deluxe’ version release warrant insights. The views of the author are their own.

“The brain processes visual information. So, the reason why people see things differently is…”

– They have different cognitions.

– Their visual acuity.

– How accurate the printout is.

When I picked up Persona 5 in 2017, I did not anticipate that it would take over a year to see the game to its conclusion. And despite the protagonists being high school kids, I also didn’t foresee partaking in micro school lessons that entailed learning real-world facts. As I progressed to P5’s exam season, it dawned on me that despite its ripe potential for engaging means of education, video games still tend to delegate pragmatic learning to what we’ve collectively deemed “edutainment.”

Super Munchers, Carmen Sandiego, and Midnight Rescue! were what kids in the 90’s had to go with. While I’m sure such games still exist in more modern contexts (Brain Age feels appropriate to mention), I can’t help but feel like the genre has petered out now that the ‘big bucks’ have been discovered by replicating the film industry. In my post-college life, I learn via YouTube essays running in the background – ironically, while I play video games. It’d be nice if we got more games that didn’t sacrifice engagement while still being able to connect us to applicable real-world knowledge.

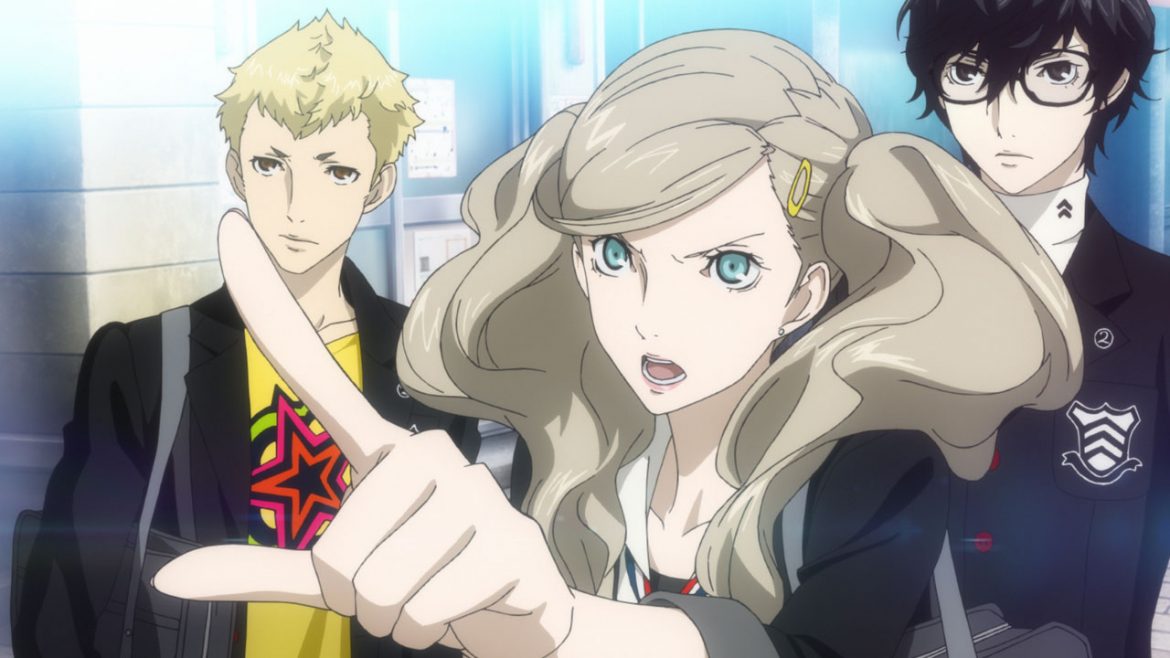

Persona 5 stands out to me in this regard because its use of ‘micro lessons’ isn’t there just to make the player feel like they’re ‘living an honest student life.’ They exist to highlight where P5’s narrative derives from. These lessons project something from reality and point a big, grouchy teacher’s finger at it, eliciting consideration of the real world. This is most apparent in how the game presents just enough info on the historical/fictional figures the primary characters’ personas are based upon.

‘Personas’ within the world of P5 are manifestations of the characters’ inner struggles, desires, etc. Personas are strengthened by real-world experiences, and awaken when characters rise up against their own fears.

Through its school lessons, Persona 5 highlights inspirations behind each primary persona – Arsene Lupin, for example, is a French ‘gentleman thief’ of 20th century literature, whom the protagonist, aka ‘Joker,’ takes cues from. But the game’s school setting also teaches tidbits about Japanese history and culture, elements which the primary narrative is rooted in by virtue of its protagonists circumstances. It even offers factoids to express its themes concerning what it means to be human.

By utilizing these snippets of class lectures and quizzes, P5 organically invites its players to ‘take their time’ in considering their lives outside the game.

To be clear, none of what I am describing bogs down the game’s pacing. These micro lessons are quick and transpire as part of the game’s weekly cycle of routine, but also happen to dole out interesting real-life information. Many other games naturally will call out literary context that their worlds and scenarios are based upon, and that trend should continue, as it does in all mediums. But different kinds of people process and retain information most effectively in different ways, so a

medium that can adapt and change to respond to those needs could be the best way to teach when individual, hands-on human time isn’t available.

Perhaps someone will some day make an RPG about someone learning how to drive, using varying characters or even stat-based mechanics and turn-based choices to help teach someone the rules of the road. The human brain attaches itself to

stories, and video games are increasingly straying outside of that limited title – ‘game’ – into the more general territory of ‘interactive software,’ yet have increasingly strayed away from anything pragmatic or informational.

Just as the culture around the medium whines at the mere mention of ‘politics,’ it has pushed itself further away from providing useful knowledge. Even Nintendo’s charming effort to teach players about the fundamentals of music was shunned at launch because it wasn’t a ‘rhythm game’ despite never advertising itself as such. Wii Music was, like Brain Age and like Wii Fit before it, not intended to be a ‘video game’ but rather to exist as software using the elements of game design toward a practical end: teaching players the basics of music and musical expression. While it is understandable that an

audience thirsting for ‘game-like content’ might not have interest, it does not make the effort pointless or inherently ‘bad.’

Persona 5 is by no means an educational game in its core intent, but it most certainly does make subtle steps at teaching its audience about real-world things its creators cared about. If developers can take notes on that use of organic context and pair it with Nintendo’s ‘Wii _‘ generation of design intent, we may yet see a future where software can educate and delight at the same time in edifying, impactful ways.

A former retail worker, storyteller, and amateur visual novel developer who grew up in western New York, lived in the SF Bay Area, and now resides in Southern England.