Work life in the ship of Among Us

Games are about rules.

Some rules are explicit while others implicit.

Think about quests in terms of rules. Players embark on quests to experience the game, where rules explicate embarking and implicate the experience from this embarking. Implications stem from explications, or drawing out meaning, while explications rely on prior implications. This has wide-ranging ramifications.

What we should focus on, for now, is how rules in games rely on notions outside of their given ruleset that gives way to implications that are shaped by rules’ explications.

“Explicit describes something that is very clear and without vagueness or ambiguity. Implicit often functions as the opposite, referring to something that is understood, but not described clearly or directly, and often using implication or assumption. To help remember, explicit things are explained, implicit things are implied.”

Merriam Webster

Among Us is such a game that implicates and explicates roles with rules.

Crewmates have to carry out chores individually and collectively while impostors must kill crewmates.

These conflicting roles appear like one another but have different goals. The task is to accomplish these goals while appearing to work towards the overarching goals of the ship.

This makes work an explicit rule common for every role. Impostors imitate this explication through implications, while crewmates engage this explication while trying to uncover impostors through the results of their actions.

Both roles demand familiarity with the implications of work to be able take part in this game of deception. We shall explore what are the implications of this centering of work.

(A)SYMMETRY

But first, think about how impostors and crewmates are symmetrical in appearance and in following rules, but asymmetrical in their goals.

This asymmetry leads to conflicts that can be resolved by a period of debate followed by a round of voting. Among Us has an explicit rule that allows debating that gives room to implicit rules of negotiation. To be able to negotiate, every member must collect information for the meeting, though how they employ it is up to each crewmate.

The subject of these debates are usually about who is and isn’t an impostor that’s followed by voting about (potentially) ejecting someone from the ship, impostor or otherwise, into the vacuum of space.

This is the crewmates’ only way to get rid of impostors: killing, that is, by means of the impostor. Such an ejection requires a plurality of votes while impostors can kill at will.

“In Among Us everyone is shaped to the image of a blue collar worker who must work even after death”

Killing is an explicit rule of the game that hinges on communication’s implications.

Work is also an explicit rule of the game that hinges on communication’s implications. Conversations introduce another set of rules with language to negotiate between the game’s implicit and explicit rules.

Asymmetry enters the game with rules external to it. Some players are better at this game of deception, others may get the rise out of others by trolling, while some games will feature players without a common tongue. Variations of communication cast a vast and wide net.

But rules considered internal to the game aren’t symmetrical either, as crewmates make the majority upon starting the game, ranging from seven to nine against one to three impostors. There’s an asymmetrical relationship in member numbers next to goals, while rule-following, appearance, debating and voting are symmetrical in themselves.

Outside the Ship

This mirrors democratic institutions, such as voting, by relying on notions of symmetry.

Through this logic of symmetry, killing serves the purpose to create symmetry in member numbers between impostors and crewmates, while voting relies on asymmetry in validating its outcome by plurality votes.

Voting, therefore, creates symmetry by way of asymmetry.

By voting, plural participants decide who gets killed, while in assassinations, it is the minority of impostors who decide. Killing is an asymmetrical force that creates symmetry towards the triumph of impostors, under the guise of positive connotations associated with symmetry.

Putting this in terms of rules, it means that explicit rules favor impostors while implicit rules offer ways to counter this in debates.

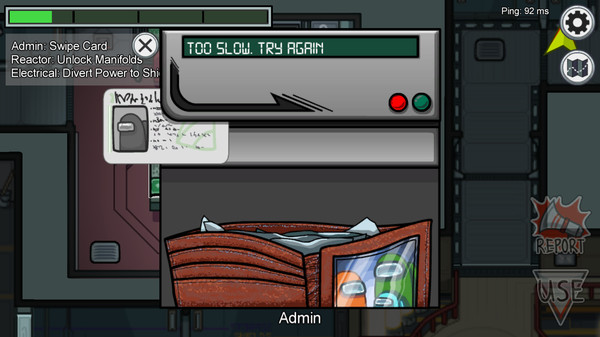

Everyone can gather information prior to debates and have the ability to participate in them by communication. We can infer, then, that crewmembers and impostors have equal access to some of these implicit rules. But crewmates have chores to complete which cover either the whole screen or large parts of it. Crewmates are constrained by work they need to carry out while impostors’ only goal is murder.

To kill, impostors need to gather information by observing what happens on the screen, further aided by the ability to hide in in vents and sabotage systems of the ship. That is to say, information needed for debates is ripe for the taking for impostors, while crewmates must toil under work, useful information potentially obfuscated by pop-ups.

This resembles a feudalist society where members of aristocracy don’t have to work to survive, allowing them to pursue other activities, while peasants must work to survive while under constant threat of death.

It isn’t different from democratic societies where privileged members can pursue political goals, unlike those less privileged who must work to survive that hinders them from pursuing political goals. Work hinders access to information to pursue political goals while lack of work benefits this access.

People who don’t work tend to be labeled as “impostors of society,” yet this lack of work allows them to be more informed about societal issues.

This makes work an explicit rule with implications that exclude. It creates asymmetry in participating in democratic institutions, such as voting, that explicitly states symmetrical participation, but creates and recreates asymmetry in its implications.

Think about how factory labor makes it difficult with its long and grueling hours for laborers to study for a different line of work.

As a consequence, children of blue collar workers have a smaller chance of participating in higher education in contrast with children from white collar families. The effects of work ripple through generations; that is to say, work’s implications become explications that lead to further implications and explications.

In Among Us, everyone is shaped to the image of a blue collar worker who must work even after death, mirroring neoliberal ideals that imagine everyone to be similar.

But it’s an illusion that depends entirely on chance, given that it’s random whether one comes to life as an impostor or as a crewmate. This birth into a crew is marred with deception that concludes to exhaustion and death.

Birth, exhaustion and death are equally valorized under the banner of neoliberal ideology, where one comes to life to survive death to which work lends a hand in equal measure. In this logic, birth and death are symmetrical in themselves that makes work symmetrical in itself too. But work is rarely seen or experienced as such, hence this logic reaffirms itself as symmetry in ways to masquerade its asymmetry.

Life and Death

It’s unsurprising that this façade brings violence into the equation with murder.

Killing unveils asymmetry just as banding together against it does. These attempts are construed by impostors and hidden by systems that introduce symmetry and asymmetry into the equitation to muddling effects. It takes time to make sense within these systems to unveil impostors, unlike work, that’s easy to learn and remember from one game to another.

This makes players replaceable, should the need rise for it, such as before the start of a game. A game of Among Us needs a certain number of players to work, otherwise it would be too asymmetrical to start. To make the game workable the players need to be symmetrical in some ways.

Labor operates in the same manner by making people replaceable should asymmetry arise.

A job vacancy is such a state of asymmetry in the production system, which is filled by workers who are symmetrical in ways to fill the vacant position. In this sense, symmetry and asymmetry sustain worker replaceability, which system lasts for generations, entrapping people in grueling and cozy work conditions under the guise of similarity.

Among Us mirrors this by making work an explicit rule of its system. This creates workers who look and behave like one another under the guise of symmetry. Asymmetry unveils this to be a facade, such as when an impostor is found during debate, or conceals it when a crewmate is thrown out to space instead.

Work remains nonetheless that makes death register only in relation to it, attested by the faceless nature of player characters, who are only remembered by their deeds.

But work is also a collective activity that creates symmetry in striving for survival.

It is to prolong living through work towards death. Its success depends on sustaining symmetry in work, negotiation and voting. Since negotiation precedes voting needed for survival, implications of asymmetry prevail in determining survival. This mostly appears to detrimental effects, as work creates conflicting goals between crewmembers, while this benefits impostors, who can reap rewards from conflicts, furthering their privilege.

Even though impostors are sparse in numbers their privilege affects implications and explications. This ambiguous appearance shapes how the system appears in function that in turn influences how the rest of the community behaves. Collective action can remove impostors from their position, but only to a temporary effect with great difficulty as long as this system that privileges a few remains.

Zsolt is a writer and critic from Hungary. You can reach him @zoltdav on Twitter.

IMAGES: Innersloth