Say it ain’t so!

As Animal Crossing: New Horizons has taken over much of our gaming existence since its launch, we have once again seen the villainization of Tom Nook, a staple punching bag of the series since its inception, but one that mischaracterizes the tanuki’s generous ways and malleable ideology.

“[T]he truth is that Tom Nook is a villain”, Den of Geek asserts, arguing that Nook is a representation of an otherwise underserved villain, the tax man. On Inverse, Nook is noted for having a “robber baron persona”, alluding to the Rockefellers and Carnegies of the world, a throwback to what some may call the shady dealings of the early 20th Century. Even SBNation, a sports site, has weighed in on Nook’s role, hailing him as an “all consuming supervillain”, echoing GamesRadar’s placement of him on their list of the best villains in video games. Heck, even I’ve argued his suggestive selling is kind of crummy.

All too often the argument centres around the premise that Nook embodies the archetypical free market capitalist, consumed by a drive to amass wealth, at yours and every other villager’s expense. This belief is so prevalent that even tweaking of the game’s interest rate–the bells paid out to the player for keeping a savings account–earned a scathing rebuke from WIRED.

It’s also a flawed belief, reliant on an education system that navel gazes at capitalism, lumping in any exchange of currency within the broad system, all while ardently refusing to acknowledge that socialism, in the democratic sense, is a system that exists and is implemented. While Nook is a far cry from the authoritarian tendencies of Pol Pot’s killing fields, Stalin’s gulags, or any other corrupted form of socialism denoted by the communist banner, he is, decidedly, socialist in nature.

Utopia

Nook is no more a manorial lord than he is a crooked capitalist: He leans much closer to the utopian socialist leanings of Robert Owen than he does any other actor, save perhaps Andrew Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth.

“Make no mistake: Tom Nook is a socialist.”

Robert Owen is perhaps best known for his mill village, New Lanark, which today is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site as a “unique reminder that the creation of wealth does not automatically imply the degradation of its producers”.

Owen was notably concerned both for his workers and for the environmental impact of his work and wealth creation. Believing in the importance of improving people’s lives, Owen set out to implement a series of reforms to the prevailing industrialist system, of which few would be considered capitalist.

Among his priorities was reducing the working hours of employees; creating public schools for children and toddlers alike, all while offering evening classes for adults; offering free medical care; establishing village stores that were stocked with goods bought in bulk at a superior quality and sold at cost; promoting self-sustainability by providing the means for tenants to plant and grow their own fruits and vegetables; promoting leisure opportunities with the creation of nature trails in the surrounding hills and even public concerts; and, finally, by empowering elected spokespersons to speak on matters concerning the greater community.

New Horizons

The above list of Robert Owen’s goals should jump out to you as similar to the laundry list of targets for what’s to be accomplished in New Horizons–where better to create utopia than on a deserted island flush with resources?–created by a businessperson with similar goals.

Education

As mentioned, education was a particular fascination of Owen’s, central to what he hoped to achieve in creating New Lanark. In his memoir, the Life of Robert Owen written by himself, he references his goals for education ad nauseum: “Another important consideration is, that all their instruction is rendered a pleasure and delight to them ; they are much more anxious for the hour of school-time to arrive than to end.”

By adopting the best educational practices, and removing children from working before age 12, Owen believes society will move forward in a kinder, gentler fashion, all while providing for everyone.

We find out, digging into Nook’s affairs in Happy Home Designer, that he is nothing if not a philanthropist, donating much of his wealth to an orphanage a few towns over. We can assume that value on children persists in Nook’s newest venture.

Tom Nook’s island doesn’t have a school: It is, in fact, possible to avoid having a child of any kind on your island.

However, one of the first tasks Nook sets the player upon is to find the necessary ingredients to allow a museum to be established. This is one of the earliest milestones in the game and with it brings a teacher-in-kind, Blathers, to contribute to island life.

The museum is a wonder with distinct sections for paleontology, entomology, and ichthyology; later on, the museum expands to include an art collection that spans the world. A museum of this scope and scale, with a curator of incredible knowledge, represents the very best in what education hopes to achieve. Disconnected from the game, people are discovering creatures like the atlas moth and the oarfish for the first time as a result of their inclusion and promotion to be studied and preserved by the museum.

The village store

While some might see it as profiteering by creating the businesses in which his employees would purchase their goods, Owen himself sought to provide the best possible goods to his workers, all while freeing them from the bondage of credit. “All the articles sold were bought on credit at high prices, to cover great risks,” Owen noted on the predatory practices, “the qualities were most inferior, and they were retailed out to the workpeople at extravagant rates.”

His solution? Buy the best possible goods in bulk and sell them at cost to the consumer, his workers, with an estimated savings of 25%.

“The effects soon became visible in their improved health and superior dress, and in the general comfort of their houses.”

It’s interesting that Owen focuses both on clothing and housing–two areas New Horizons players are given great agency–tying them to the health of the population.

It should also come as no surprise that the two permanent shops on your island have close connections to Nook. Nook’s Cranny, the island’s general store, is operated by his two young apprentices, Timmy and Tommy, who provide staple goods in their back cupboards along with a rotating selection of housewares, ranging from coffee grinders to gigantic bear plushies. The young tanuki will also buy anything offered to them, from weeds to tin cans, as an incentive to help keep the island clean for the inhabitants.

Then there’s the Able Sisters’ Tailor Shop: While not directly Nook affiliated, it’s hard to imagine a new shop opening without his blessing. Sable, the prickly seamstress, was at one point a close friend and confidant of his, with effusive praise come from the otherwise quiet hedgehog. That the only permanent clothing shop on the island is a friend of Nook’s suggests he cares for the quality being offered to his island’s residents, and, through the Able sisters, he can exert some influence over what’s offered. All other clothing purchases come from Nook’s catalogue, which also offers a range of goods for enhancing the island itself, all offered straight from Nook.

Representatives

In Owen’s New Lanark, the village was divided into 12 divisions, with each local group voting on a representative to serve on what is effectively town council. One of the residents, Lorna Davidson, remarked the council met to “discuss village affairs and also to adjudicate in cases of dispute between neighbours”.

Similarly, Tom Nook understands that as his remote island is developing, he can’t represent the wishes of everyone. The player is named Island Representative while he brings in Isabelle to help support his work, with one of her primary focuses mediating disputes between the islanders. That there isn’t a whole council, or that it’s always the player who is chosen to be representative, is result of the game state, rather than some nefarious attempts by Nook to maintain control.

The representatives at New Lanark were often referred to as ‘bug hunters’. They weren’t after the removal of tarantulas and scorpions like on the island: Rather, they inspected homes for cleanliness, a particular fixation of Owen’s, but one that is somewhat backed up in New Horizons by the purchase of weeds and other waste at Nook’s Cranny. Plus, you can literally hunt bugs and sell them, so there’s that.

Leisure and Sustainability

At New Lanark, Owen spared no expense to ensure the citizens were given opportunities to enjoy leisure and, in doing so, provide to the sustainability of the village. Residents were given the means to grow various fruits and vegetables, both for their wellness and to promote the beauty and maintenance of the valley, a step that will have echoes in Animal Crossing.

He created extensive pathways and nature trails in the surrounding hills. The nomination for New Lanark to become a World Heritage Site includes a description of “[c]arefully sited riverside paths, bridges and viewpoints have been combined with judicious planting”. Concerts, too, were planned for the workers, housed in the formidable Institute for the Formation of Character, which was primarily used as a school during the day.

Each of these aspects has parallels in Animal Crossing, from the collection of fruit on a daily basis, to the post-game ability to terraform the island and receive permits for various pathway types, and signify that this is a place of leisure as much as it is a place of enterprise.

Consider the endgame of Animal Crossing: New Horizons — Tom Nook wants the island to be successful enough to attract the talents of KK Slider to perform a concert. That’s it: that’s how you “beat” the game, if such a state exists. To accomplish this goal involves improving your island–surely at an expense of time and labour–and in doing so it doesn’t enrich Nook.

Indeed, even the regularity of KK’s concerts, occurring each Saturday thereafter, stresses the leisure based goal of it all. If that wasn’t enough, Nook recently went to elaborate lengths to celebrate May Day, creating a maze island as a recreational activity for his island’s inhabitants.

Criticisms

There’s no shortage of criticism that can be levied at Tom Nook, particularly in past games, as he can appear to be unscrupulous at times. Nintendo producer Aya Kyogoku acknowledges this in an interview with cnet, “Tom would just go ahead and expand the home without even checking in with the player, so maybe the impression that the players got back then was that he was money-hungry and he was always out to get your money.”

Nook himself is aware of his reputation. In Happy Home Designer he outright calls himself a “boogeyman” that other residents can “unite against”. It’s water off a duck’s back, for Nook, who has managed many successful enterprises by this stage in his career.

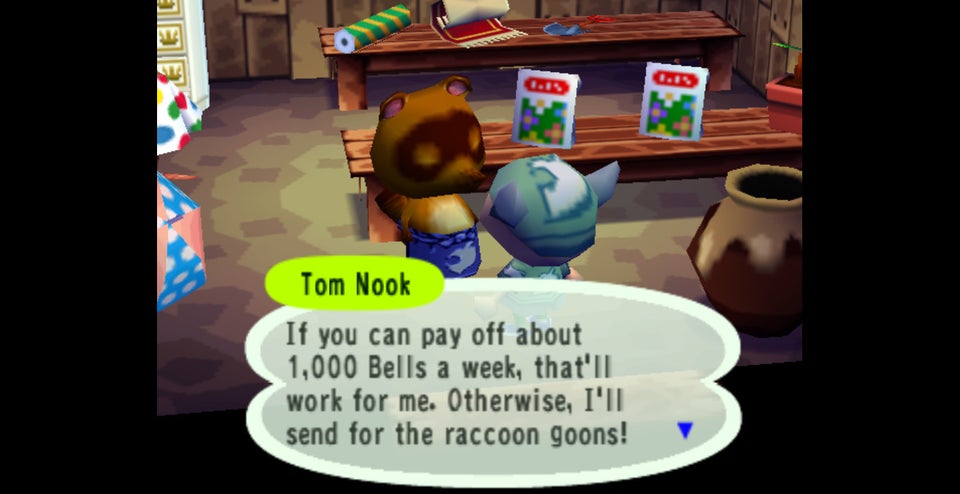

Of course, there’s no forgiving some of Nook’s earliest transgressions, notably shaking down players who didn’t pay up in a timely fashion, threatening a visit from “raccoon goons”.

Owen himself engaged in somewhat shady practices, though his were more focused on his labour relations, in which he publicly ranked the performance of his workers by rotating a coloured block. A “bad” performance was denoted by black, blue signified “indifference”, “good” by yellow, and white represents excellence.

Such a public appraisal would be rightly condemned today. Owen took it further: he recorded, in great detail, these performance appraisals, releasing six volumes a year. Owen doubles down on this system, describing the response of his employees, “ I could at once see by the expression of countenance what was the colour which was shown. As there were four colours there were four different expressions of countenance most evident to me as I passed along the rooms.”

Owen actively sought to improve the efficiency and record keeping capabilities of his operations–a trait shared by Nook, if you check out his office space–believing that his profits can be best utilized to benefit the inhabitants of New Lanark. If he’s still considered a socialist, one of the forefathers of the system, then Nook is a natural fit alongside him.

Check this out: The Scottish Maritime Museum has a 3D reconstruction of Owen’s punishment system, the silent monitor.

Other criticisms

Perhaps the most apt criticism of Animal Crossing: New Horizons, and, by extension, Tom Nook, comes from The Independent’s Louis Chilton. He argues the game–especially through its Nature Day event–encourages something more akin to imperialism than environmentalism.

During the game, the bounties of nature quickly become commodities, to be hoarded, sold and repurposed in the name of progress. Forests are razed for the wood to build garden tables; fish are dredged from the rivers to be sold at the local shop.

His critique is more pointed when it comes to discussing visits to the game’s mystery islands, where players are encouraged to pillage everything in sight, leaving a wasteland of holes and stumps behind.

Dreams before money

It’s really up to each player to make their own decisions about whether Tom Nook is a hero or villain; it’s a discussion that’s raged on for years and is unlikely to wind down anytime soon.

Through the lens of psychology, CheckPoint argues that Nook is trying to create the best community he can to replace missing emotional bonds, a criticism that is hard to refute, but one that is in no way generous to Nook’s intentions.

Utopian socialism, as espoused by thinkers like Robert Owen, is an attempt to gently and morally persuade capitalists to transfer the means of production to the people. It’s a long game, and one never fully realized by the likes of Owen, but it’s hard not to compare Nook and Owen.

If we insist on applying the capitalist lens then we must do so generously. Andrew Carnegie, a robber baron to some and a captain of industry to other, famously wrote his Gospel of Wealth, advocating that as a result of wealth inequality, the best off in society must spend thoughtfully and generously in the public interest. Like Owen, he was also fixated on education, and much of our existing system, predicated on the so called “Carnegie unit”, is owed to him. Indeed, Carnegie’s Gospel likely inspired the much more modern “Giving Pledge”, made relevant by the likes of Bill Gates and Warren Buffet.

It’s no wonder that Nook is hailed as a villain when we’re programmed, from the very beginning of our interactions with the market, to cast socialist systems as booygemen in their own right. Every step of the way Nook subverts and bends the capitalist system we know and are comfortable with–interest free loans, a free museum, plentiful opportunities for leisure–so when he does engage in what might be capitalist behaviour it feels out of place.

It feels wrong.

We’re not familiar enough with the language of economics to label Nook anything more than a greedy capitalist when in reality the Tom Nook of today is anything but one.

Perhaps the best eye to cast upon Tom Nook comes from his longtime friend, Sable: “His call to arms, his ethos, was ‘Dreams before money!’ He was so pure that people wondered if he’d survive this crazy old world. I did too.”

Tom Nook has survived. And through everything he’s been through he’s evolved, and changed, and quietly improved for himself and for his adopted family and community.

Make no mistake: Tom Nook is a socialist.